Paramedicine After Curfew

May 28, 2021

Today marks one year since I started working as a paramedic — a hands-on job dependent on teamwork, leadership and decision-making during oftentimes intense medical or traumatic interventions. I never would have imagined, at the age of 22, that I would find myself delivering a baby on a bathroom floor, ventilating an unconscious child or having to explain to the wife of a 40 year old patient that nothing could be done to save him. As paramedics, we see every stage of life, are welcomed into every type of home, and hear every story imaginable.

The memorable calls are always the ones out of the ordinary. How many times has a stranger told you with full sincereness that they happened to fall and get a broomstick stuck in their butt? Or has a stranger ever recited "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" type Vogon poetry to you on the way to the hospital? I feel pretty honoured to have gotten such odd glimpses into others' lives. Well, I could definitely manage without the poetry... I'm still not sure how to "properly" react to being told by a stranger "I love you like the sun loves the sand, I love you like the wind loves the trees, I love you like the rocks love the moon". The only word I managed in return was "Okay".

The most unsettling part is hearing the last words of a patient. When this happened again last week, the man's broken sentence was buried behind our CPAP and Salbutamol nebulizer, his exposed chest only covered in defibrillation pads. He had waited 12 hours before seeking help, thinking his sudden and inexplicable onset chest pain and respiratory distress would pass. He was actually having a heart attack causing pulmonary oedema with intense hypoxia. In movies and on TV, death is portrayed as a peaceful and almost beautiful passing as the family cries. If only reality were like that.

One key distinction between paramedics and nurses is that as paramedics we have to also stabilize the environment. Usually the situation is chaotic when you first get on scene and you need to be able to take control of the case, guide coworkers, decipher the patient’s symptoms, and evacuate. The most important part is just making a decision. There’s no time to hesitate, so initiate something, later you can take a step back to brainstorm with your partner.

Speaking of the partner, this is the person you spend close to 50 hours with every week in a small enclosed environment. The connection you have is indescribable, your life is in their hands and together you experience some unimaginable things; it truly is just you and your partner versus the rest of the world.

I love the sirens, the partnership, and being able to guide strangers during their most vulnerable moments. To be a paramedic you need to be comfortable with the unknown no matter the situation since there’s no way of entirely predicting what will happen on scene. I’ve opened patients’ doors to find a semi-conscious person with the top of their head intentionally blown off, pools of blood, and decomposing bodies, but also sweet elderly people unable to get up off the ground on their own and parents concerned for their newborn who just ate too fast. Every call is a gamble and I’m addicted.

What surprised me the most when starting the job was just how chaotically good my colleagues are. It takes a certain level of absurdity to willingly seek what others consider “the worst day of their lives.” To me it’s fascinating to observe the delicate balance of different personality traits needed in what is a pretty rough job. As a paramedic you need to work quickly but not rushed, be patient yet stern, sympathetic but not take things personally. You are oftentimes expected to have superhuman abilities and do everything at once. For a grieving family, this stress sometimes manifests as anger and assault which, for me, is the hardest part of the job.

One of the only other things that affects me is when I feel taken for granted. Paramedicine is a fairly young profession and certainly a misunderstood one, so a big part of not feeling "used" is by educating the public of what we are capable of doing. As primary care paramedics in Québec, we now carry life-saving medications for cardiac chest pains, severe dyspneas, opioid overdoses, anaphylactic reactions, and hypoglycaemias. We're also able to complete electrocardiograms and send them directly to the awaiting hospital, intubate unconscious patients, suction, use the CPAP and Oxylator, immobilize patients after a high-velocity impact or fracture, provide oxygen and wound care, and evacuate patients on our stair chair or backboard. The takeaway is that we specialize in high variance potentially life-threatening interventions and situations where reduced mobility is preventing the patient from getting to the hospital. In critical situations, we contact the emergency room team directly so that they're expecting us. 9-1-1 is maybe not the best option at 5am for the constipation you've been having for the past 3 days without first contacting your pharmacy to try laxatives. This actually happens fairly often and is perhaps the motivation behind my article, other than my love for documenting events to reminisce about.

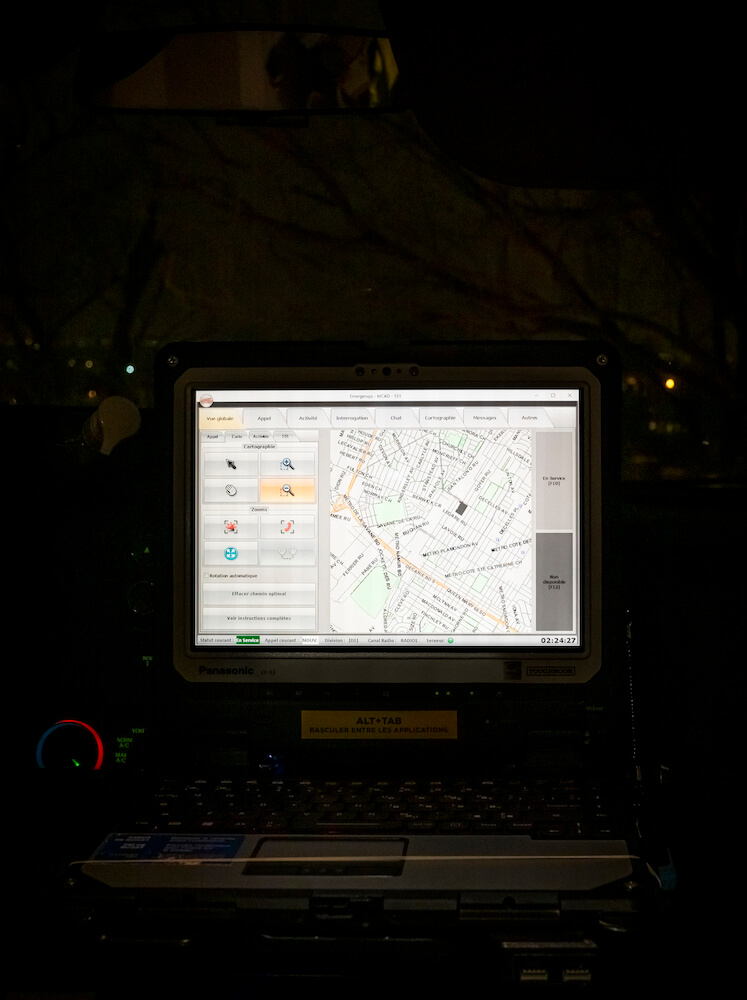

The different elements of the job start to flow together after around the four month mark working, especially the driving with lights and sirens while simultaneously navigating through unmarked construction zones using a laggy computer running on Windows XP, as well as dealing with radio-communication in French and with 10 codes. Fluidity during interventions improves with time as you begin to be able to predict what equipment and resources are needed to improve the pace such as knowing when to ask first responders to make room for evacuation and bringing tools from the ambulance. Communication is key, so constantly remind yourself to speak loudly and slowly, making sure that everyone understands what needs to get done and when. It can certainly feel overwhelming at times, and adding a pandemic into the mix is no help.

It’s wild to look back on our approach to fighting infectious diseases before COVID-19. We would regularly treat patients with pneumonia with oxygen and nebulized salbutamol in only our surgical masks. Now, as soon as a patient presents with a dyspnea, cough or fever, we wear our full PPE: gown, 2 pairs of gloves, P100 mask with filters, and visor. The same is true if the patient is unconscious as manual ventilation and circulation (ie chest compressions if the patient has no pulse) create aerosols. No matter the symptoms, we now enter every scene with our surgical masks on and immediately ask the patient and their family members to put them on too. Our cleaning product has been upgraded to a rough bleach/chlorine mix which is also destroying our wiring systems. I always prep a few sheets with the mix at the start of the shift so that I can easily clean my tools and the patient’s cards on scene as I work. This pandemic has made me more aware of how I manipulate my equipment as to minimize risk of cross contamination.

Today actually also marks the end of curfew in Québec. With the consistent drop in the number of COVID cases throughout the province, the lockdown between 9:30pm and 5am will no longer be in effect. Restaurant terraces are opening, kids are biking, and picnics on Mount Royal are in full swing. I can't wait to finally be able to hug my friends and family.